This article first appeared in the Medical Independent November 29, 2021

By MARION SLATTERY, ANDREW DUNNE

Advances in exercise specificity are having a direct impact on clinical signs and features of Parkinson’s disease

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old male presented for a clinical exercise prescription (August 2020), having been referred by his consultant neurologist. The patient was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in August 2017. In the years preceding diagnosis, commonly referred to as the prodromal stage of the disease, the patient initially presented to his GP with insomnia (since confirmed as an REM disorder), constipation, depression, and anxiety.

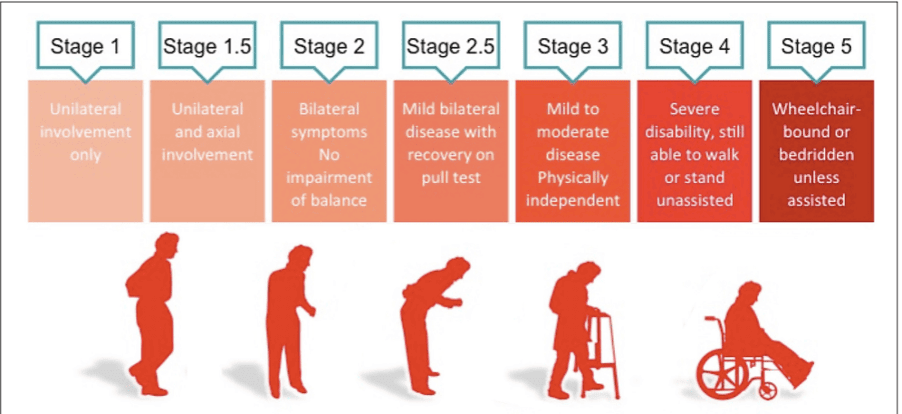

He developed a mild tremor in his right hand in early 2017 and was subsequently referred to a consultant neurologist. He is currently classified as stage 2 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale, a commonly used system for describing how the symptoms of PD progress, meaning he has unilateral involvement only, with minimal functional impairment. He had a difficult period in terms of low mood when originally diagnosed.

However, he reported working through these issues and described his mental health as stable. On presentation for an exercise programme his primary concerns were weight gain (centrally), some cervical and lumbar spine discomfort, and a perceived loss of power in his golf swing.

He was particularly concerned that the deterioration in his golfing performance was due to a ‘global’ loss of strength secondary to a progression in his PD. Prior to his clinical exercise intervention, the patient did no formal exercise other than casual walking and a weekly round of golf. Due to reduced arm swing and some deterioration in gait quality he had noticed that a round of golf took him approximately 20-to-30 minutes longer compared to pre-diagnosis.

The patient is currently employed as a civil engineer. When first diagnosed, he was anxious to keep the information private – being primarily concerned at how his competency levels may be perceived. However, he has since disclosed this information to his employer, who has proven very supportive and reassuring.

During his initial assessment, he subjectively described difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs). Objectively, there was a generalised reduced amplitude in movement, notably gait cadence, arm swing, micrographia (handwriting), touch and scroll usage of his laptop, and difficulty with fine motor tasks (such as buttoning his shirt before going to work).

The patient had no inclination that these ‘smaller’ issues could be improved by exercise. He has two teenage daughters. He is motivated to maintain a good quality-of-life and reduce the impact or severity of PD where possible. He has a good relationship with his GP and neurologist.

The exact cause of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is unknown. However, ageing, genetics, and our environment are all likely to play a role as composite factors. It is uncommon that the disease is diagnosed before the age of 50 years, but the incidence increases five-to-10 fold from the ages of 60- to-90 years. PD is a chronic, progressive neurological disorder characterised by signs and symptoms, such as bradykinesia, hypokinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, postural instability, and difficulties with gait. PD is a form of Parkinsonism, which is an umbrella term for other neurodegenerative conditions including multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, Lewy body dementia, and corticobasal degeneration.

These Parkinsonism conditions are typically referred to as atypical Parkinsonian disorders, with similar core features to PD, yet varying clinical signs that lead to differential diagnoses. The most commonly observed motor deficits associated with PD are due to degenerative change in the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway of the midbrain. In a PD patient there is a resultant reduction in the amount of dopamine produced. Inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction also contribute to the disease process. The progression of the disease is succinctly described by the Hoehn and Yahr (HY) staging scale (Figure 1).

Ongoing medical management

Currently the case report patient in this article is taking Sinemet 25mg, a levodopa-carbidopa combination medication. The levodopa changes into dopamine upon entering the brain which most noticeably has an effect on his resting tremor. From a musculoskeletal perspective he also feels that it alleviates some cervical and lumbar stiffness. The carbidopa component may have helped to reduce some unpleasant side-effects, such as nausea when first prescribed Sinemet.

To this end the patient no longer experiences these symptoms. The patient is also taking rasagiline (0.5mg), a monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitor. The MAO-B enzyme is a catalyst that triggers a chemical reaction, ultimately preventing dopamine levels from getting too high in a person.

Therefore an MAO-B inhibitor prevents this process happening in a PD patient who requires increased dopamine. Caution and vigilance is encouraged around how rasagiline can interact with some commonly-used prescription and over-the-counter medications.

The patient was prescribed fluoxetine by his GP to help manage low mood, which has proven effective. Additional medications include melatonin for disturbed sleep and occasionally a short-term course of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) for cervical and lumbar discomfort. Finally, the patient takes a stool softener

(senna) as required.

He was referred by his GP for MRI imaging at cervical and lumbar levels on separate occasions in the last 18 months. Overall the reports were non-remarkable, suggesting mild degenerative disc disease at C3-4, C4-5, L4-5, L5-S1 levels, with no evidence of canal stenosis or narrowing at exit foramina bilaterally. On his most recent neurology appointment he was referred for a clinical exercise programme, specifically to address general movement and fine motor deficits which had recently become impactful at work.

Figure 1 : Hoehn and Yahr Scale

Exercise prescription as part of the medical treatment plan

The most recently published (high-quality) peer-reviewed literature is suggesting amplitude of movement ought to be a primary focus in PD exercise prescription. These advances in exercise specificity are having a direct impact on clinical signs and features of the condition, in the same way medication has been impactful to date.

In plain language, the exercises ought to have a greater focus on quality and amplitude of movement (as opposed to generic strength and conditioning) in a bid to enhance this patient’s handwriting, laptop usage, self-dressing, and walking, which are essential to his sense of wellbeing.

According to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines (2021), “ultimately the exercise prescription in this case should appear to slow the rate of disease progression.” Rigorous measurement of neuromotor development is a challenge for the exercise specialist and neurologist alike. In this regard, accurate observation and functional comparisons are deemed sufficient. Secondary considerations ought to include the ACSM ‘FITT’ guidelines to best address cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), flexibility, muscular strength and endurance in the PD patient.

How do I make my exercise prescription specific?

With amplitude of movement prioritised, it is now worth adding specificity to the exercise prescription. The Lee Silverman Voice Training (LSVT) BIG programme is an exercise treatment consisting of large amplitude movements and exaggerated movement patterns (Figure 2). The exercises are performed with high intensity and effort that becomes progressively more difficult and complex, with the overall goal of restoring ‘normal’ movement amplitude in real-life situations. This programme results in ‘moments of calibration’ as it were, whereby normal pre-Parkinson’s movement patterns are restored.

LSVT BIG has been proven effective for motor function impairments in people with PD, when compared to control groups (performing generic, aerobic and resistance exercise programmes). Other relevant specific exercise programmes exist, including PD Warrior. In general, if a clinician is embarking on a PD exercise programme with a patient, it needs to include a variety of challenging physical activities (eg, multidirectional step training, step up and down, reaching forward and sideways with maximal speed and effort, obstacle courses, turning in standing and supine).

These exercises demand an intensive neuroactive response, promoting neuroplasticity, dual tasking, balance and coordination. It is incumbent on the clinician to have ‘had their Weetabix’ as regular demonstration, rhythmic auditory, and verbal cueing is a vital part of the process!! (anecdotally we can report these workouts are also high-level intensity for non-PD patients).

Resistance training is recommended twice weekly to avoid secondary complications of PD such as muscle wastage. Free weights can be used in the case of this article’s patient due to his mild/moderate presentation. At more advance stages of the disease, overhead resistance training with free weights can become unsafe due to increased severity of tremor.

Therefore, weight machines, and other resistive devices (such as pulleys and resistance bands) may be safe alternatives to free weights. At all stages of PD, lower limb strength training is indicated, with modifications dependent on presentation. Attention should be given to extensor muscles of the trunk and hip to counteract postural decrements.

Continuous aerobic exercise can challenge even the most motivated athletes; therefore the modality should depend on patient preferences, with an emphasis on enjoyment if possible. If the patient enjoys the aerobic components of the programme, it is far more likely to become a consistent part of their lifestyle. In this regard, anything from treadmill, elliptical trainer, recumbent bicycle, aqua aerobics, outdoor hill walking, tango, or waltz dancing are all evidence-based interventions for aerobic benefit.

Finally, flexibility and range of motion (ROM) exercises can be active (patient alone) or passive (clinician assisted). Typically there is an emphasis on spinal mobility and axial rotation. In this case the patient included a daily cervical, thoracic and lumbar mobility routine incorporating Tai Chi type movements throughout, with the assistance of a guided DVD.

Case report patient update

The patient has worked intensively for 15 months on a hybrid exercise programme. Body composition has changed with a small increase in lean muscle mass, and a cumulative weight loss of 7kg. He has reported significant improvement in ADLs such as shirt buttoning, laptop usage, handwriting, reaching and rotating in general. Most importantly for the patient, he has regained some speed and torque in his golf swing, and is also able to keep up with the pace of his peers in between shots. His neurologist has encouraged him to remain as active as possible.

Summary and recommendations

On presentation for an exercise programme, the case report PD patient had no inclination that some of the clinical features of Parkinson’s could be addressed through exercise specificity. These neuromotor changes proved to be a significant source of motivation, renewed vigour and confidence for the participant. An exercise prescription needs to be as equally specific as a medical prescription, in terms of frequency, intensity, duration, dosage and type. In modern medicine it is vital that exercise prescription is included as a key part of the medical treatment plan.

References on request

You can book an exercise session with us on our website or call 01 496 4002.