By Eoin Keating, Ruairi O’Donoghue, Mark Hynes, Andrew Dunne, October 26, 2021

This article orginally appeared in the Medical Independent October 2021.

While the management of osteoarthritis is multifactorial, including surgical, pharmacological, and lifestyle interventions, there is overwhelming evidence to prioritise exercise prescription as best practice in the management of this condition.

CASE REPORT 1

A 64-year-old female with a history of right knee total knee replacement (TKR) in 2016 (patella preserved), presents with gradual-onset left knee pain and is worsening with activity. She has a long-standing diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and subsequent Barrett’s oesophagus, so is taking longterm proton pump inhibitors (PPI).

The patient is not willing to pursue injection therapy or a surgical route at present due to unsatisfactory outcomes following her right knee TKR. She is also currently on the beta blocker bisoprolol 5mg daily and this has proven effective in reducing blood pressure. Patient is mildly asthmatic with no prescribed inhaler.

The patient is recently retired from employment as an accountant and keen to pursue an active outdoor lifestyle. However, she is highly frustrated re same due to persistent pain levels in left knee joint. Despite this the patient is now persisting with regular golf (minimum two x 18 holes per week) and taking over the counter (OTC) paracetamol to alleviate symptoms.

She is also walking approximately 3-5km as often as possible – pain allowing (usually three times per week). She tends to complete her walk with a significant limp secondary to increased pain levels. Discomfort at night is causing broken sleep due to an associated low-level ache, but this has been persistent for approximately six weeks. As a result, symptoms of fatigue and volatile mood swings are becoming regular.

Peak pain levels in her left knee are subjectively scored at 8/10 on exertion and 3-4/10 at rest using the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NRS).

Symptoms are best alleviated by 24-to-48-hours rest at present or getting into the sea for a five minute ‘dip’. An x-ray of the left knee taken in October 2018 suggested chronic degenerative bony change in the medial aspect, with a diagnosis of early stage osteoarthritis.

Most recent left knee MRI reports degenerative change in the knee and patellofemoral joint. There is thinning of articular cartilage in the medial compartment. There is a stable tear in the mid body of the lateral meniscus. There is a probable small ganglion cyst at the anterior aspect of the tibial insertion of anterior cruciate.

Pathogenesis – what is this ‘wear and tear’ we refer to…

Initially, osteoarthritis has been considered to be a disease of articular cartilage, but recent research has indicated that the condition involves the entire joint. The loss of articular cartilage has been thought to be the primary change, but a combination of cellular changes and biomechanical stresses causes several secondary changes, including subchondral bone remodelling, the formation of osteophytes, the development of bone marrow lesions, change in the synovium, joint capsule, ligaments and periarticular muscles, and meniscal tears and extrusion.

Trauma in the knee joint can lead to increased inflammation. This can lead to a slight increase in enzymatic activity. This in turn may allow the formation of ‘wear’ particles, which could be then engulfed by resident macrophages. At some point in time, the production of these ‘wear’ particles overwhelms the ability of the system to eliminate them and they become mediators of inflammation. This process sets chondrocytes in motion to release degradative enzymes. And so the process of ‘wear and tear’ has begun.

Initial degenerative changes in the articular cartilage lead to cartilage softening, fibrillation of the superficial layers, fissuring and diminished cartilage thickness. These changes can become more pronounced with time, when articular cartilage thins to total destruction, eventually leaving the underlying subchondral bone plate completely exposed.

However, phrases like ‘bone-on-bone’ are misunderstood in terms of clinical presentation – whereby prognostic indicators around future activity levels, function and overall quality-of-life cannot be determined by imaging alone.

At this juncture a patient with no gastric history would typically benefit from a short- to medium-term course of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, in the case report, the patient cannot benefit from such an approach due to the long-term PPI for GORD/Barrett’s oesophagus. Her usage of OTC paracetamol is also proving ineffective. A discussion around the benefits of intra-articular joint injection has not yielded a positive response based on her chequered history with the right TKR.

So it is now appropriate to address modifiable behaviours. Rest assured this can be done in a succinct and timely fashion. The most obvious place to start is to address current activity/ exercise levels. In this case it is abundantly clear that current activity levels are playing a role in aggravation of the troublesome joint, contributing to pain levels. Before we prescribe exercise, a risk stratification and review of medications is appropriate. The patient has no personal or family cardiac history.

As a stand-alone strategy, the prescription of a beta blocker drug to reduce blood pressure has proven effective. Systolic and diastolic pressures in supine were reduced by 11.7mmHg and 10.4mmHg, respectively. However, with a beta blocker this means an otherwise healthy heart is beating with less speed and force.

Accordingly, in order to facilitate a more accurate exercise prescription, there is a coherent clinical argument to change blood pressure medication. An alternative such as a calcium channel blocker will allow for safe return to more elevated heart rate zones during exertion. It also allows for greater accuracy when using heart rate as a reference point for exertion (eg, subjective outcome measures such as the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE)).

Having assessed for risk factors, an adjustment in medication to a calcium channel blocker (amlodipine x 5mg per day) now allows for an accurate target heart rate to be calculated for the patient’s exercise prescription.

Exercise prescription as part of the medical treatment plan

Having explored the options around medical and orthopaedic intervention it is now apparent that this patient prefers conservative management. Lifestyle intervention is often cited as a challenging area for medics due to the information provided being vague. It is best practice to consider that an exercise prescription falls under SMART guidelines –

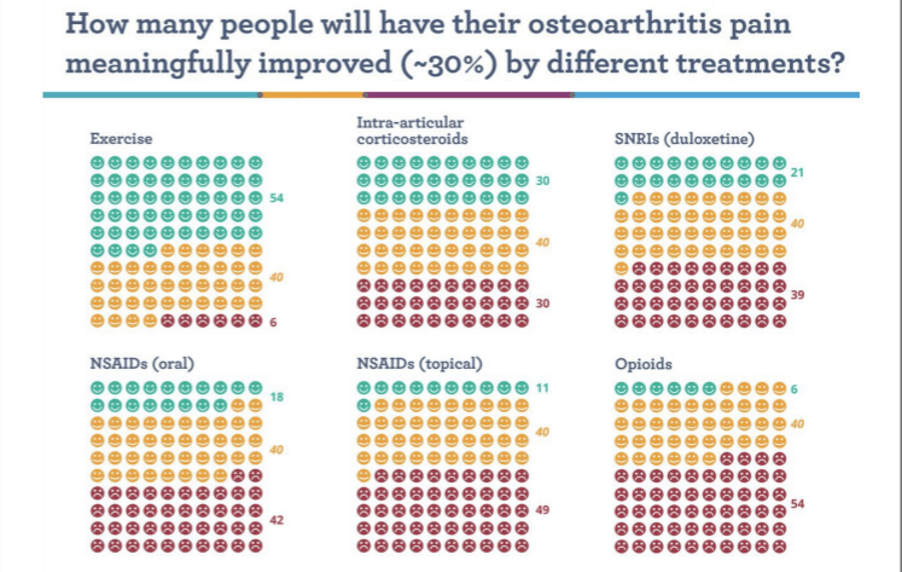

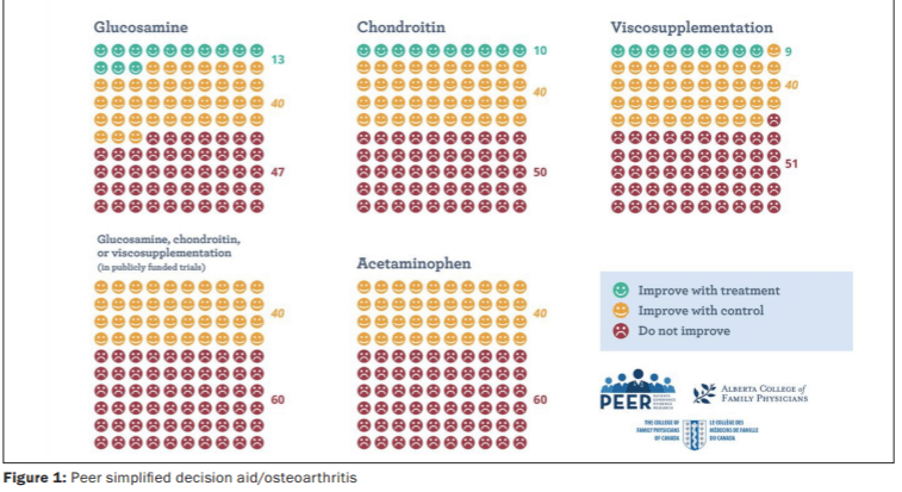

Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Targeted. Similarly, in order to reduce osteoarthritis-associated pain levels the prescribed exercise needs to enhance function without causing further aggravation. This is a key factor for the patient and most likely a challenge too for the prescribing medic – given the time constraints in a regular consultation. The evidence base is unequivocal for exercise prescription having a beneficial effect on osteoarthritis-related pain levels (see Table 1). While this ought to be reassuring for the attending doctor, it is also a vital tool in reassuring and motivating the patient.

How do I make my exercise prescription specific? 220 – = heart rate max 220 – <64> = 156bpm

World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines for vigorous activity = 70-85 per cent of heart rate max for 75 mins per week. Thus the target heart rate zone for ‘vigorous’ activity per week is 109-133bpm x 75 mins per week.

In the case report patient, it is also important to modify and reduce current activity levels as a component part of the exercise prescription. The patient is cumulatively walking up to 25km per week on an angry knee. She needs to reduce total walking by an estimate of 80 per cent in order to allow the inflamed knee some rest and recovery. However, this needs to be replaced by low-impact resistance training. Here the focus is on strengthening the soft tissue structures around the knee.

As strength levels improve, unnecessary guarding (or avoidance of use of the affected knee) can be diminished with simple gait assessment and cueing. Furthermore, continuous or interval based aerobic activity (such as recumbent bike or elliptical trainer) can have a significant effect on reducing pain levels through release of anti-inflammatory myokines.

The combination of aerobic intervals and low-impact strength training is proven to regenerate synovial fluid and enhance production of hyaluronic acid, both of which are significantly impactful for inflammation at a cartilaginous level.

So the final exercise prescription can be summed up in a succinct and measurable way as:

1. 109-133bpm x 75 mins per week preferably achieved through a mix of low-impact strength training and aerobic interval training

2. Reduction of cumulative walking distance by 80 per cent from 25k to 5km in week one.

3. In week two-to-six, walking distance progression to increase by 10 per cent per walk, provided symptoms are improving.

It is not commonplace that the doctor will have sufficient time to provide such specificity around exercise prescription. Therefore, it is incumbent to refer to a chartered physiotherapist who specialises in clinical exercise prescription. Furthermore, research shows that supervised exercise programmes are proven to be more effective than non-supervised exercise, in terms of outcomes and achieving stated goals.

Case report follow-up

So what of our case report patient? She has recently celebrated her 66th birthday. Playing golf twice per week, with a subjective pain score (NRS) 2/10 at peak levels. At rest, patient is only symptomatic for approximately 24-hours immediately post the second round of golf per week, but feels OTC paracetamol is sufficiently impactful as a remedy. She also reports improved sleep quality, has lost 4lbs in weight and is generally more active in activities of daily living (ADLs). Reports significant improvement in quality-of-life.

Summary and recommendations

It is widely acknowledged that there is an implementation gap in clinical practice with regard to exercise prescription. Most cited barriers to implementation are time constraints and lack of content in the undergraduate medical curriculum. This can lead to a lack of awareness around the literature supporting the benefits of prescribing exercise.

Exercise advice should be considered, specific and measurable. Anecdotally there is a prevalence of ‘vague’ lifestyle advice in practice, and as such patient outcomes away from the clinical setting can be diminished. In order to maximise the medical rehabilitation potential of the patient it is strongly recommended that the referring medic and chosen physiotherapist collaborate in the provision of an exercise programme.

References on request

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Conor McCarthy (Rheumatologist), Dr Barry Sheane (Rheumatologist), and Dr Fergal McNamara (GP) for reviewing this article.

You can book an exercise session with us on our website or call 01 496 4002.